ǀ English ǀ Español ǀ Français ǀ Italiano ǀ Português ǀ Русский ǀ

- The Uprising in Kazakhstan (CrimethInc.)

- A Color Revolution or a Working-Class Uprising? (Zanovo Media)

- Protests in Kazakhstan: 5 clues to understand what’s going on (Communia)

- Kazakhstan: The Working Class Attempts to Find its Voice? (Internationalist Communist Tendency)

- Statement by Russian anarcho-syndicalists and anarchists on the situation in Kazakhstan (KRAS)

- Kazakhstan: strikes and riots teeter the regime (International Communist Party)

- “The people will still have an opportunity to rid the country of a dictator” (Pramen)

- Kazakhstan after the Uprising (CrimethInc.)

- In Kazakhstan the working class has shown what it is capable of doing and what it will do (International Communist Party)

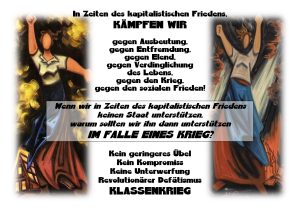

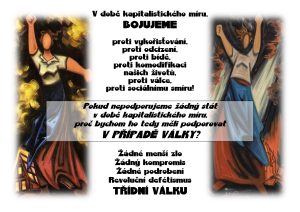

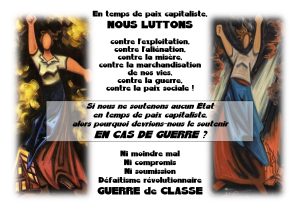

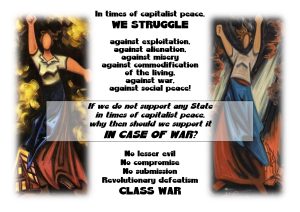

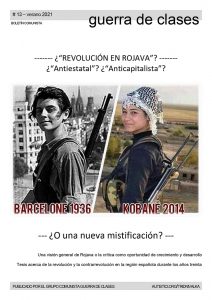

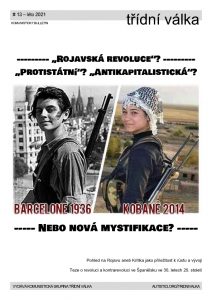

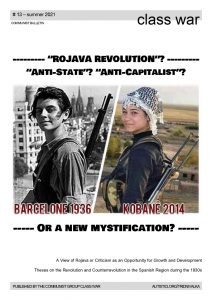

Class War’s Presentation

Listing the countries where social unrest breaks out becomes a real “Prévert-style inventory”, as many collective movements of our class took shape and gained strength these last months throughout the world. Like a taste of Sulphur floating in the air, like a wildfire… No need to say but it’s so great to glimpse this old world completely blowing apart!

Through spasmodic and (all too often) heterogeneous movements the proletariat raises its head in all latitudes, under every pretext, no matter the exact nature of the attack against our living (survival) conditions under the dictatorship of capital, no matter if the government is leftist or rightist, no matter all the “reasons” given by all the media, all the negotiators, all the social peacemakers, and even sometimes (often!) by the proletarians in struggle themselves…

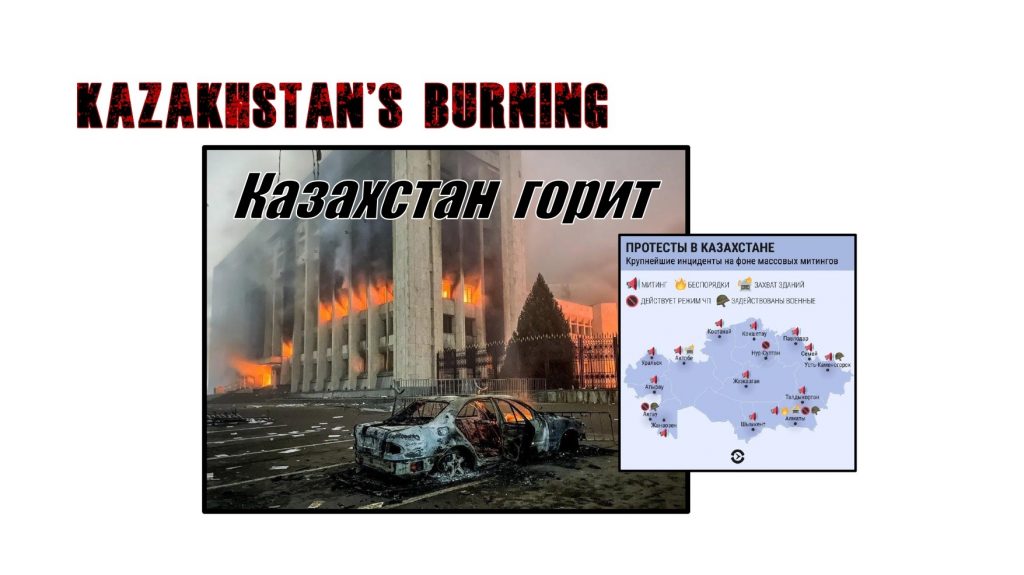

Early January 2022, it was Kazakhstan’s turn to enter the dance: a state of emergency was declared throughout the country following very violent demonstrations, occupations and burning of government buildings, road blockades, strikes, among others (but not only) in Almaty, officially against the rise in fuel prices and against the high cost of living in general. We even saw police officers putting down their helmets and shields in front of the demonstrators as an act of defeatism and deserting to the side of the struggling proletariat. Within a few days, within a few hours, our class brothers and sisters stormed the citadels of capital by instinctively re-appropriating their class gestures…

But, they are too isolated and, while carrots do not delude them any longer (contrary to other factions of the proletariat in other parts of the world), they were in return terribly beaten with sticks by a hard-pressed bourgeoisie, aided in this by units of the Russian special forces, in charge of the dirty work in restoring social order. Everything is back to normal and normality is in everything, as we usually say in such circumstances. Nevertheless, the direct intervention of the Russian regional gendarme allows us to imagine (in spite of the few militant information that reaches us) the extent of the defeatism that must have affected the units of the Kazakh police and army, unable to restore order.

We present hereafter a series of militant texts that report somehow on the events and can give an idea of what happened in Kazakhstan. The fact that we publish these texts does not imply in any way that we would adhere to the whole of the analyses developed in them and even less to the programmatic positions of the groups and individuals who produced them.

Class War – January 2022

The Uprising in Kazakhstan

An Interview and Appraisal

Source: https://en.crimethinc.com/2022/01/06/the-uprising-in-kazakhstan-an-interview-and-appraisal/

ǀ Deutsch ǀ Español ǀ Français ǀ Italiano ǀ Polski ǀ Português Brasileiro ǀ Русский ǀ 中文 ǀ

A full-scale uprising has broken out in Kazakhstan in response to the rising cost of living and the violence of the authoritarian government. Demonstrators have seized government buildings in many parts of the country, especially in Almaty, the most populous city, where they temporarily occupied the airport and set the capitol building on fire. As we publish this, police have recaptured downtown Almaty, killing at least dozens of people in the process, while troops from Russia and Belarus arrive to join them in suppressing the protests. We owe it to the people on the receiving end of this repression to learn why they rose up. In the following report, we present an interview with a Kazakhstani expatriate who explores what drove people in Kazakhstan to revolt—and explore the implications of this uprising for the region as a whole.

“What is now happening in Kazakhstan has never happened here before.

“All night there were explosions, police violence against people, and some people burned police cars, including some random cars. Now people are marching around the main streets and something is happening near Akimat (the parliament building).”

—The last message we received from our comrade in Kazakhstan, an anarcha-feminist in Almaty, shortly before 4 pm (East Kazakhstan time) on January 5, before we lost contact.

We should understand the uprising in Kazakhstan in a global context. It is not simply a reaction to an authoritarian regime. Protesters in Kazakhstan are responding to the same rising cost of living that people have been protesting all around the world for years. Kazakhstan is not the first place where an increase in the cost of gas has triggered a wave of protests—exactly the same thing has happened in France, Ecuador, and elsewhere around the world, under a wide range of administrations and forms of government.

What is significant about this particular uprising, then, is not that it is unprecedented, but that it involves people confronting the same challenges we confront, too, wherever we live.

The urgency with which Russia is moving to help to suppress the uprising is also significant. The Collective Security Treaty Organization [CSTO], a military alliance comprised of Russia, Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan—with Russia calling the shots—has committed to sending forces to Kazakstan. This is the first time that the CSTO has deployed troops to support a member nation; it refused to assist Armenia in 2021, during its conflict with Azerbaijan.

It is instructive that the war between Armenia and Azerbaijan did not warrant CSTO intervention, but a powerful protest movement does. As in other imperial projects, the chief threat to the Russian sphere of influence (the “Rusosphere”) is not war, but revolution. Russia has profited considerably from the civil war in Syria and the Turkish invasion of Rojava, playing Syria and Turkey against each other to gain a foothold in the region. One of the ways that Vladimir Putin has held on to power in Russia has been by rallying Russian patriots to support him in wars in Chechnya and Ukraine. War—perpetual war—is part and parcel of the Russian imperial project, just as war has served the American imperial project in Iraq and Afghanistan. War is the health of the state, as Randolph Bourne put it.

Uprisings, on the other hand, must be suppressed by any means necessary. If the millions of people in the Rusosphere who languish under a combination of kleptocracy and neoliberalism saw an uprising succeed in any of those countries, they would hurry to follow suit. Looking at the waves of protest in Belarus in 2020 and in Russia a year ago, we can see that many people are inclined to do so even without hope of success.

In capitalist democracies like the United States, where elections can swap out one gang of self-seeking politicians for another, the illusion of choice itself serves to distract people from taking action to bring about real change. In authoritarian regimes like Russia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan, there is no such illusion; the reigning order is imposed by despair and brute force alone. In these conditions, anyone can see that revolution offers the only way forward. Indeed, the rulers of all three of those countries owe their power to the wave of revolutions that took place starting in 1989, bringing about the fall of the Eastern Bloc. We can hardly blame their subjects for suspecting that only a revolution could bring about a change in their circumstances.

Revolution—but for what purpose? We cannot share the optimism of liberals who imagine that social change in Kazakhstan will be as simple as chasing out the autocrats and holding elections. Without thoroughgoing economic and social changes, any merely political change would leave most people at the mercy of the same neoliberal capitalism that is immiserating them today.

And in any case, Putin will not give up so easily. Real social change—in the Rusosphere as in the West—will require a protracted struggle. Overthrowing the government is necessary, but not sufficient: in order to defend themselves against future political and economic impositions, ordinary people will have to develop collective power on a horizontal, decentralized basis. This is not the work of a day or a year, but of a generation.

What anarchists have to contribute to this process is the proposal that the same structures and practices that we develop in the course of the struggle against our oppressors should also serve to help us create a better world. Anarchists have already played an important role in the uprising in Belarus, showing the value of horizontal networks and direct action. The dream of liberalism, to remake the entire world in the image of the United States and Western Europe, has already proved hollow—the United States and Western Europe are implicated in many of the reasons why efforts to realize this dream have failed, in Egypt and Sudan and elsewhere. The dream of anarchism remains to be tried.

In response to the events in Kazakhstan, some supposed “anti-imperialists” are once again parroting the timeless talking point of Russian state media that all opposition to any regime that is allied with Putin’s Russia can only be the result of Western intervention. This is particularly egregious when the nations in Russia’s sphere of influence have largely abandoned any pretense of socialism, giving themselves over to the sort of neoliberal policies that sparked the revolt in Kazakhstan. In a globalized capitalist economy, in which we are all subjected to the same profiteering and precarity, we should not let rival world powers play us off against each other. We should see through the whole charade. Let’s make common cause across continents, exchanging tactics, inspiration, and solidarity in order to reinvent our lives.

The ordinary people in Kazakhstan who rose up this week showed how far we can go—and how much further we have to go together.

Russian forces leaving for Kazakhstan.

The Background of the Uprising

Early on January 6 (East Kazakhstan Time), after internet blackouts made it impossible to complete an interview with participants in the movement in Almaty, we conducted the following interview with a Kazakhstani anarchist advocate living abroad.

For context, what anarchist, feminist, and ecological projects or movements have existed in Kazakhstan in the 21st century?

Early on, there was an opposition to the first ex-communist president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, who ended up leading post-Soviet Kazakhstan. Beginning in the 1990s, he started becoming more authoritarian—for example, dismissing a more political plural parliament twice in 1993 in order to obtain loyal members of parliament, extending his first presidential term, and changing the structure of governance to acquire stronger executive powers through referendums that were deemed rigged in 1995. This earned Nazarbayev opponents within the political elite itself from across a wide political spectrum including Communists, Social Democrats, Centrists, Liberals, and Nationalists who collaborated to call for a more democratic constitution with limited presidential authority and a multi-party legislature.

As for movements from below, there were anarchists, who were more of an underground movement, and there was a unusually loud socialist movement group, whose leader Ainur Kurmanov ended up fleeing Kazakhstan in the end. There were nationalists and radical Islamists as well, but again, they weren’t really that prominent and they too were sort of underground.

As for environmentalists, if they did have some public attention through media or promotion, it was mostly from advocacy groups or, as they’re called “public associations” there. In Kazakhstan, only six political parties are registered by the government right now, and they are the only ones legally permitted to participate in general elections; the others that have tried to form political parties end up seeing their required registration processes systematically rejected by the ministry. However, whenever the Kazakh authorities do in some circumstances proclaim their political pluralism to the public, they make a show of this using loyal public associations, especially during presidential elections.

Are there any opposition parties in Kazakhstan?

Regarding opposition parties, there are basically none in Kazakhstan that are deemed legal. There used to be such independent functioning political parties back in the 1990s and early 2000s, but they were all shut down or banned by the government, along with independent press and media. Today, there are people who claim to represent the opposition, but they live abroad in countries such as Ukraine. They have no real connection to the street.

There is also some sort rivalry within them: I’ve heard all of them accusing each other of collaborating with the government or intelligence agency. A typical characteristic of the controlled opposition in Kazakhstan is that the so-called declared oppositions try to lure dissatisfied citizens into doing things that don’t actually pose any threat to the government, things that give the illusion of making change, like telling people to engage in peaceful dialogue with local officials or to participate in the election by purposefully ruining the ballot as a way to “protest”—any tactic that gives the illusion of fighting the government, when in reality it is just a waste of time.

In recent years, this sort of opposition actually started to appear inside country, as well; out of nowhere, there were random activists forming political movements and holding pickets without experiencing any form of persecution, whereas ordinary people who have no connections are always detained by police immediately whenever they tried to protest.

One unusual opposition group—I can’t tell whether it is controlled opposition—is called Democratic Choice of Kazakhstan. It is led by a former businessman and politician living in France named Mukhtar Ablyazov. If you search his name, you’ll see articles about supposed money laundering cases and lawsuits. He was a cabinet minister in the 1990s, until he broke ranks with the government that was predominately loyal to President Nazarbayev. He was jailed by the Kazakh government, but eventually released; he ended up fleeing from Kazakhstan and living in exile like other disloyal officials of Nazarbayev’s. Since then, he has led the political opposition with the most support on social media. Most anyone associated with his movement has been persecuted and arrested; this has been happening ever since he re-established the movement again in 2017 on various social media platforms. Every protest he has organized from abroad has been repressed, with a massive police presence in public areas. There have been cases in which the internet was partially restricted nationwide.

In any case, what is happening in Kazakhstan now is completely unexpected.

What tensions within Kazakhstan preceded these events? What are the fault lines in Kazakh society?

What really sparked the mass unrest took place in the town of Janaozen. This town produces oil profits, yet the people there are among the poorest in the country. The town is known for the bloody events of December 2011, when there was a labor strike and the authorities ordered the police to shoot demonstrators. Although the tragedy ended quietly, it still remained in many Kazakhs’ minds, especially among the town’s residents. Since then, more small strikes have taken place there in the oil industries—though those were peaceful and didn’t lead to bloodshed. Since 2019, strikes and protests have become more common there. At the same time, due to economic factors, people have become more active in politics across country as oil prices plunged worldwide, impacting Kazakhstan economically. As the Kazakhstani currency—the tenge—became weaker, people could afford less and less.

There are also serious problems in Kazakhstan: lack of clean water in villages, environmental issues, people living in debt, public mistrust, corruption and nepotism in a system in which any objection can easily be shut down. Most people have gotten used to living in these conditions while the economy has served billionaire oligarchs who have ties with government officials and other prominent people. In the early 2000s, people in Kazakhstan had a glimpse of hope as the economy grew thanks to natural gas reserves; as a consequence, many people’s standard of living rose. But it all changed in 2014, when oil prices dropped worldwide and the war in Ukraine led to sanctions against Russia—which impacted Kazakhstan, since it is dependent on Russia.

There were some small protests from 2014 to 2016, but they were easily suppressed. From 2018 to 2019 they grew more, thanks in part to the aforementioned opposition businessman, Mukhtar Ablyazov, who used social media to gain traction. Political protests and activism were organized under the banner of the Democratic Choice of Kazakhstan party. This did lead to longtime President Nazarbayev resigning after ruling for almost three decades, but he had his position taken over by his long trusted ally, the current President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev. Tokayev barely received any trust from Kazakh citizens; he was viewed as Nazarbayev’s political puppet, as he barely took any steps towards widely demanded reforms and took no executive action against government officials that the public despises.

Kazakhstan’s political system and President Nazarbayev’s leadership have defined Kazakhstani society for the entire history of its independence. I mentioned before how Nazarbayev basically became an authoritarian ruler via various means that catalyzed the opposition against him. Under Nazarbayev, the Kazakh government had never allowed any actual opposition statesmen to challenge him through the country’s presidential or parliamentary elections. The rest of the politicians and legal parties that were contestants in the elections were simply different people with different faces but the same pro-government stances, all as a poorly implemented illusion to make Kazakhstan look like a “democratic” country in which one strongman and his ruling party happen to win every election with an unconvincing, even surrealistic majority of votes—despite documented cases of electoral fraud. This is similar to the situation in Russia, Belarus, and other dictatorial post-Soviet countries. As time passed, things really got dire as a cult of personality was created around Nazarbayev. The government spent millions in state budget naming and erecting streets, parks, squares, airports, universities, statues, and the capital city of Astana after him. All this accomplished was to irritate the public more, making Nazarbayev look like a narcissist.

The situation in Kazakhstan became worse after 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. People lost their jobs; some were left without any way to pay for goods, receiving very little support whatsoever from the government, while health restrictions made people more frustrated and distrustful of the government. And then the price of goods rose for food specifically—this has taken place worldwide, but for Kazakhstan, it had a considerable impact.

To return to the town of Janaozen, which has a history of bloodshed, the price for liquefied gas skyrocketed—in the very place where the fuel is actually produced. That cost has grown steadily for the past ten years, but it finally increased even more when the government stopped subsiding it, instead letting the market decide.

There had already been small protests about this issue in that city—but on January 1, 2022, the price for the liquefied gas that is used to power vehicles unexpectedly doubled. This enraged people. They protested in the square in massive numbers. Law enforcement seemed hesitant to disperse the protest. Other villages in the province rose up and started blockading roads in protest. Then, in a few days, the protests spread nationwide.

What started with a protest over the hike in gas prices grew largely because of the other problems I mentioned previously. These motivated people to go out on strike and into the streets more.

Describe the different agendas of the different groups on both sides of this struggle. Are there identifiable factions or currents within the demonstrations?

At first, the government ignored the gas price problems by trying to get people used to it, even blaming consumers for the high demand. Eventually, they lowered the price, but this didn’t stop the protests. Then the state essentially denied their involvement in letting the gas prices inflate—but as the protests intensified, the government began to concede more to try to calm people down. For example, they pledged to introduce some policies to offer people economic assistance, after ignoring them for years.

But the protests still haven’t stopped. Few people trust or support the government. The people demonstrating simply want a better life, like they imagine people have in developed European countries. Of course, there are different demands from different people—some seek the resignation of the entire government, while others want a new form of democratic government, specifically a parliamentary form without an executive president, and still others want more jobs and industry and better social conditions.

Some of the fiercest rioting and looting is taking place in the old Soviet capitol of Almaty, which is the financial metropolis and the largest city in Kazakhstan now. People are looting stores and setting things on fire. They have burned down the Almaty administrative building (or akimats, as they are referred in Kazakhstan) in front of the central square, as well as the law enforcement headquarters.

In my view, the government has contributed to this situation, because they haven’t fulfilled the demand to resign peacefully and let an opposition-run interim government form a new democratic political system. The current president of Kazakhstan, who is a close ally of the former and first president, Nazarbayev, is adding fuel to the fire by refusing to transfer his power. The longer he holds on to his position, the more violence will occur, since neither the government nor the protesters can compromise. As long as this goes on, the people who are doing violent acts will be able to continue to get away with it. There’s lawlessness in Almaty; it seems that nobody is sure who’s in charge there now, since the mayor’s office was burned down and he disappeared from public view. The entire city is barricaded with armed protesters walking around.

The city is under a curfew, in theory, but in practice, law enforcement is absent or has joined the protests—so the city is like a commune [i.e., as in the Paris Commune] from what I hear. At this point, considering how the events are unfolding, I wouldn’t call the people there protesters, but revolutionaries—especially seeing armed civilians there.

In response, the government which presides at the country’s capital of Nur-Sultan (or Astana) has send various security “anti-terror” forces to take control of the city, turning the usually peaceful town into a nightmare war zone.

Present a chronology of the events of the past week.

The protest started in the oil-producing town of Janaozen on January 2. By the next morning, other cities and villages in western Kazakhstan had begun protesting in solidarity.

The most massive protests took place at night as the unrest spread to other cities, including Almaty. Late at night on January 4, people in Almaty marched to the main square in front of city hall. Huge troops of police were positioned there. Clashes broke out, but the protestors got the upper hand.

They were dispersed early in the morning of January 5, but they regrouped again by around 9 am in the foggy morning. Some law enforcement officers even switched sides and joined the protest as videos from social media show. Eventually, the protesters marched to the square again around 10 am and managed to storm the city hall, setting the building on fire. Government security officers fled Almaty, leaving the city under the control of the protesters.

Since then, President Tokayev sent some troops there again in an attempt to take control via a “terrorist cleaning” operation. I don’t how it’s playing out at every minute, but I’ve seen on social media that during the night of January 5 or early in the morning of January 6, things in Almaty became chaotic as people started looting and breaking into weapons’ deposits in order to obtain them and gunshots were reported.

In other cities, it’s more peaceful, with massive protests in the central squares. I heard unverified information that some protesters have taken over the local government buildings in a few other cities, but as far as I know, those are less chaotic compared to Almaty.

In the capital, Nur-Sultan, it is quiet, but people have witnessed huge numbers of riot police surrounding the Aqorda presidential palace. Basically, the entire place is now a fortress.

In short, all Kazakhstan is now like The Hunger Games. If you have seen the Hunger Games trilogy or if you know a basic summary of the plot, you know what I’m talking about. Protestors are attempting to take control of various cities one by one in an attempt to topple the government. Again, incumbent President Tokayev doesn’t want to hand over power. If that doesn’t happen, I expect the chaos to continue until the government is overthrown or the uprising is brutally suppressed, or some even worse scenario.

Do you think the participants in these protests have any reference points for the protest movements that have broken out in France, Ecuador, and elsewhere around the world in response to increasing fuel prices? What is informing the tactics they are using?

I think a lot of them are influenced by the protests that have taken place in other post-Soviet countries like Belarus and Kyrgyzstan. It seems that in Almaty, the residents drew on the example of neighboring Kyrgyzstan, where people also stormed the government and burned down buildings—but compared to Kyrgyzstan, the government was overthrown more quickly. (In my view, this was partly due to it being a smaller country with just one major capital city.) Kyrgyzstan has experienced three revolutions so far; considering its close proximity and cultural ties to Kazakhstan, since both countries speak Turkic languages, I think its example has played a significant role in Kazakhstan.

What are the possibilities for what will happen next?

From my point of view, I can imagine a couple scenarios. Either the government resigns – or is overthrown – and Kazakhstan starts down the path to democratization, or the government suppresses the uprising with a tremendous use of force, including involving other countries. Or an even worse scenario – a prolonged and destructive civil war between the government and rebelling Kazakhs.

The president of Kazakhstan, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, is asking the CSTO [the Collective Security Treaty Organization, a military alliance comprised of Russia, Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan] to send in “peacekeeping” soldiers. In short, the president is inviting foreign troops into Kazakhstan to try to suppress the protests. Either the armed protesters somehow repel these forces and the government falls, or the revolutionaries give up and are crushed.

Kazakhstan faces a dark future. It’s a war for liberty or defeat, and defeat would mean a potential loss of more liberties and possibly sovereignty.

What can people outside Kazakhstan do to support the participants in the struggle?

The only realistic way for people outside in Kazakhstan to support is by bringing more attention to the events and maybe organizing some sort of aid.

Conclusion: A View from Russia

In the following text, a Russian anarchist reflects on the implications of the uprising in Kazakhstan for the region. You can read a perspective from Belarusian anarchists here.

After decades of repression, failures, and defeats, why is hope rising again and again, as we see in Belarus, Russia, Kyrgyzstan, and now in Kazakhstan? Why, after our relatives, friends, and neighbors fall, shot dead by the police or the army, do people still struggle? How is it that we still get these chances to experience the wind of change and excitement, which gives us a taste of all that our lives could be?

We can feel some answers in the lines of Kazakh musician Ermen Anti from a band named Adaptation:

“No matter how much they shoot, the bullets won’t be enough.

No matter how much they crush, nevertheless the seedlings

Of fair anger are sprouting up

Prometheus children, carrying fire to the people freezing cold.”

When we look at the events of the past decades in Kazakhstan, Belarus, Russia, and Kyrgyzstan, we need to ask what cooperation between initiatives and movements struggling towards liberation could accomplish on an international level. Such connections could enable us to exchange political and cultural experiences, to strengthen the common cause which the people of these countries should share. Yet in contrast to how much the economies and political realities of these countries are interconnected and interdependent, the anarchist movements are disconnected.

Kazakhstan can be an example for what can happen tomorrow in Russia, Belarus, and other countries in this part of the world. Today, people in Russia fear for their lives when they think about expressing any form of dissent. But tomorrow, we can see Zhanaozen and Almaty in the cities of Russia, Belarus (again!), and other countries. We can forget about the assurances that “It can’t happen here”—what can and cannot happen depends first and foremost on what we can imagine and desire.

When situations unfold like what we see today in Kazakhstan, we can see how important it is to be connected with others in our society. Today, we are surprised—we often might not even be among the people in the streets, fighting and defending each other shoulder to shoulder, or doing other important work to support the uprising. To be ready and connected, we need to be able to face the contradictions within our communities and within our society as a whole. We need to be able to communicate our ideas and bring proposals to people around us in situations like these. Conflicts, disagreements, and isolation are smothering comrades who could otherwise dedicate their lives to the struggle. When I ask myself what is needed for us to see each other in the streets and in people’s homes, walking together, caring for each other and fighting together, I imagine us approaching each other in different way—making it possible for each other to struggle, to develop, to survive.

We can ask ourselves: what do we need to change in how we approach each other and other people, how do we approach the struggle and our movements, in order to make them a source of life and inspiration that can offer people ways to think, fight, and live?

For example, we remember the feminist movement in Kazakhstan, which was the center of the public attention and discourse for some years in the 2010s, which published a feminist magazine and brought up that topic in Kazakhstan in ways that no one had before, connecting a lot of groups and communities along the fault line of domestic violence and patriarchy. This is an example of how we can position ourselves to address issues that will connect us to a wide range of other people in our society.

We in the ex-Soviet republics have an impressive heritage of resistance and uprisings to draw upon. We need to connect to each other so we can access this heritage.

Solidarity and strength to everyone fighting in Kazakhstan and across all the post-Soviet countries. As people say, the dogs may bark but the caravan shall go on. Today, they may stomp on our necks, but the struggle won’t cease, and those who fell in the streets of Almaty won’t be forgotten.

A Color Revolution or a Working-Class Uprising?: an Interview with Aynur Kurmanov on the Protests in Kazakhstan

Source in Russian: https://zanovo.media/kategorii/habeas-corpus-2-2/massovye-vystupleniya-v-kazakhstane-tsvetnaya-revolyutsiya-ili-vosstanie-rabochego-klassa/

English translation: https://lefteast.org/a-color-revolution-or-a-working-class-uprising-an-interview-with-aynur-kurmanov-on-the-protests-in-kazakhstan/

LeftEast gratefully acknowledges Zanovo-media, where this article was originally published in Russian.

Today all post-Soviet mass-media and TV channels are riveted to the protests that suddenly engulfed Kazakhstan. To some they arouse hope, to others – horror and rejection. There are contradictions and different interpretations of what is happening: righteous people’s protest, clan wrangling, conspiracy of pro-Western and pro-Turkish forces or even “Islamist reaction”. But what is really happening? A Zanovo-media correspondent interviewed Aynur Kurmanov – one of the leaders of Socialist Movement of Kazakhstan.

A model republic

Kazakhstan is one of the biggest post-Soviet countries, which is only second to the Russian Federation in that system of political and economical relations, which was built after Soviet collapse. And this is not just because Nursultan Nazarbayev was one of the architects of the CIS (Commonwealth of Independent States). The Kazakh model of smooth transformation of former party and Soviet nomenclature into a capitalist oligarchy with “an Asian face” was seen by many as a model. Indeed, this model had superficially attractive features not only for the ruling elites in other republics, but also for the average citizen: a high economic level, the presence of formal attributes of democracy, and few restrictions on Western culture. Large reserves of natural resources, including oil, and the industrial potential inherited from the socialist period proved a good launching pad for the young state. At the same time, the official propaganda of the Russian Federation and the CIS channels liked to set Kazakhstan as an example of preserving “the union traditions”, honoring the memory of the Great Patriotic War, the absence of nationalism, and so on.

Mass protests broke out immediately after the New Year holidays, on January 2. The reason for protests was the rise in price of liquefied gas for cars, from 60 tenge to 120 tenge per liter. The first unsanctioned demonstrations began in the west of Kazakhstan, in the Mangistau region, the heartland of large oil-producing enterprises. It is here that the notorious Zhanaozen is located, where ten years ago a workers’ strike was brutally suppressed: 15 strikers were killed and hundreds injured in Zhanaozen.

On the next day – January 3 – the protesters in the Mangistau Province added new social and political points to their initial demands: reduction of food prices, taking measures against unemployment, solution to the drinking water shortage, resignation of the government and local authorities. On this day, the protesters also began to gather in the squares and streets of Almaty, the capital city Nursultan and other cities. In a number of places, roads were blocked and protesters did not disperse even at night.

On Tuesday, January 4, protesters clashed with police. In Alma-Ata, security forces used stun grenades to disperse protesters. In turn, protesters overturned police cars. In the evening of the same day, mobile Internet, messengers and social networks stopped working.

Kazakhstani authorities tried to explain the gas price increase by the fact that its price is now determined by electronic bidding. As they say, “the market has decided”. The administration of the Mangistau Region firmly stated that everything was within the frames of the modern market economy, and the previous price was not coming back.

But on January 4, under pressure from the protesters, the government was forced to lower the price of gas in the Mangistau region to 50 tenge per liter. The President of Kazakhstan Kasim-Jomart Tokayev said that the rest of the demands of the population would be considered separately. And then on January 5, the current Cabinet of Ministers was dismissed. The director of the gas processing plant in Zhanaozen was detained.

Region of total poverty

The co-chairman of the Socialist Movement of Kazakhstan Aynur Kurmanov described the situation in the following terms:

The workers of Zhanaozen were the first to rise. An increase in the gas price served only as a trigger for the popular protests. After all, the mountain of social problems has been accumulating for years. Last fall, Kazakhstan was hit by a wave of inflation. It should be taken into account that products are imported to the Mangistau region and they have always been 2-3 times more expensive there. But on a wave of rising prices at the end of 2021, the cost of food rose even more, and substantially. We must also take into account that the West of the country is a region of solid unemployment. In the course of neoliberal reforms and privatization, most of the businesses there were shut down. The only sector that still works here are the oil producers. But for the most part, they are owned by foreign capital. Up to 70 percent of Kazakhstan oil are exported to western markets, most of the profits also go to foreign owners.

There is practically no investment in the development of the region: it is an area of total poverty and poverty. And last year these enterprises began to undergo large-scale optimization. Jobs were cut, workers began to lose their salaries, bonuses, many enterprises have turned into just service companies. When in Atyrau region the company Tengiz Oil fired 40 thousand workers at once, it became the real shock for the whole Western Kazakhstan. The state did nothing to prevent such mass layoffs. And it should be understood, that one oil worker feeds 5-10 family members. Dismissal of a worker automatically condemns the whole family to starvation. There are no jobs here except for the oil sector and sectors that service its needs.

Kazakhstan has actually built a raw-material model of capitalism. The population has accumulated a lot of social problems, there is a huge social stratification. The “middle class” is ruined, the real sector is destroyed. The uneven distribution of the national product has a considerable corruption component. Neoliberal reforms have all but eliminated the social safety net. And most likely, the owners of transnational corporations calculated – 5 million people are needed for servicing the “pipe”; the whole 18+ million of Kazakh population is too much. And that’s why this revolt is anti-colonial in many ways. The causes the current protests are rooted in the workings of capitalism: price of liquefied gas really rose on electronic trades. There was a conspiracy of monopolists who benefited from exporting gas abroad, creating a shortage of it and an increase in gas prices on the domestic market. So they themselves provoked the riots. However, it should be noted that the current social explosion is directed against the whole policy of capitalist reforms that have been carried out over the last 30 years and their destructive results.

Traditions of Workers’ Struggle. Spontaneous Strike

The form of protest initially was a classic “proletarian” strike. On the night of 3 to 4 January, a wildcat strike began at the Tengiz Oil enterprises. Soon the strike spread to neighboring regions. Today, the strike movement has two main focus points – Zhanaozen and Aktau.

As conspiracy theorists write today, the unrest in Kazakhstan was carefully prepared in the West, as evidenced by the careful organization and coordination of the protesters. In Kurmanov’s words:

This is not a Maidan, although many political analysts are trying to present it this way. Where did such amazing self-organization come from? This is the experience and tradition of the workers. Strikes have been shaking the Mangistau region since 2008, and the strike movement began back in the 2000s. Even without any input from the Communist Party or other leftist groups, there were constant demands to nationalize the oil companies. The workers simply saw with their own eyes what privatization and foreign capitalist takeover was leading to. In the course of these earlier demonstrations, they gained enormous experience in struggle and solidarity. The very life in the wilderness made people stick together. It was against this background that the working class and the rest of the population came together. The protests of the workers in Zhanoazen and Aktau then set the tone for other regions of the country. Yurts and tents, which protesters began to put up in the main squares of the cities, were not at all taken from the “Euromaidan” experience: they stood in the Mangastau Region during the local strikes last year. The population itself brought water and food for the protesters.

In Kazakhstan today there is no legal opposition, the entire political field has been cleared. The Communist Party of Kazakhstan was the last to be liquidated in 2015. Only 7 pro-governmental parties remained. But there are plenty of NGOs working in the country, which actively cooperate with the authorities in promoting a pro-Western agenda. Their favorite topics: the famine of the 1930s, the rehabilitation of participants of the Basmachi movement and collaborators of World War II, and so on. NGOs also work on the development of nationalist movement, which in Kazakhstan is completely pro-government. Nationalists hold rallies against China and Russia which are sanctioned by the authorities.

According to our interlocutor, the sinister Islamists allegedly behind the recent events are also extremely weak and poorly organized in Kazakhstan. As he assured us, in fact, modern Kazakhstan is committed to building a mono-ethnic state, and nationalism is its official ideology. All reports of “pro-Soviet” Kazakhstan by the likes of Mir TV channel are a myth:

Back in 2017, a monument was erected in Kyzyl-Orda to Mustafa Chokai, the inspirer of the Turkestan legion of the Wehrmacht. Today, the state is radically revising history. The process has especially intensified after Nursultan Nazarbayev’s visit to the USA a few years ago. The pan-Turkic movement is also becoming more and more active. More recently, i[on the initiative of Nursultan Nazarbayev, the Union of Turkic States was established in Istanbul on Nov. 12, 2021. Kazakhstan’s elite keeps its main assets in the West. That’s why the imperialistic states are absolutely not interested in the downfall of the present regime; it is already completely on their side.

But perhaps not everything is so unambiguous with the geopolitical priorities of Kazakhstan? It seems that its leadership all the same tends to conduct notorious multi-vector policy, maneuvering between Russia, the West, China and Turkey. But one condition suits all foreign partners here – the local “loyal” legislation allows foreign companies to take the profits out of the country. However, if possible, none of the global players will stop at changing the government into an even more obedient one. And, of course, the liberal opposition will try to establish and is already establishing its control over the mass protest movement.

Nazarbayev’s resignation as president to head the Security Council was motivated by the desire to create the appearance of democracy, including to the West. In reality, he maintains full control over all the branches of power and only increased his power while at the same time completely avoiding responsibility. President Tokayev is a decorative figure, a pawn within the ruling family. Undoubtedly, the current protests can lead to some factions attempting a palace coup or similar actions. You can’t reduce everything to conspiracy theories. You shouldn’t idealize the current protest movement either. Yes, it is a grassroots social movement, with a pioneering role for workers, supported by the unemployed and other social groups. But there are very different forces at work in it, especially as workers do not have their own party, class trade unions, a clear program that fully meets their interests. The existing left-wing groups in Kazakhstan are more like circles and cannot seriously influence the course of events. Oligarchic and outside forces will try to appropriate and or at least use this movement for their own purposes. If it wins, the redistribution of property and open confrontation between various groups of the bourgeoisie, a “war of all against all,” will begin. But, in any case, the workers will be able to win certain freedoms and get new opportunities, including the creation of their own parties and independent trade unions, which will facilitate their struggle for their rights in the future.

Kazakhstan’s armed forces try to confront the protesters

P.S. After the article was published, it became known that in Almaty and some other cities there are heavy clashes, the protestors have seized many key infrastructure buildings in Almaty and other cities. Under pressure from the protests, President Tokayev made unprecedented social concessions – he promised state regulation of gas, gasoline and socially important goods, a moratorium on raising utility bills, subsidized rents for housing for the poor, and the creation of a public fund to support health care and children. Protesters also demanded a return to the 1993 Constitution and a government made up of people outside the system. And they still demand lower food prices and a reduction of the retirement age to 58-60, higher wages, pensions, child benefits, and so on.

Liberal opposition activists hastened to declare that it is they who coordinate the movement.

By the evening of January 5, it was reported that Nursultan Nazarbayev was no longer the chairman of the SB. President Tokayev took his place and stated his intention to act “as tough as possible. At the same time, it was promised that “consistent political reforms” would soon be carried out.

Later on that day Takayev called for a “peace-keeping” (in fact, police) operation of the Collective Security Treaty Organization countries (Russia, Belarus, Armenia, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan) to suppress the protests, which the Kazakh were now declaring an attempt of intervention from outside. By the morning of January 6, CSTO council had approved of the request and there are already reports of Russian troops in Kazakhstan.

Protests in Kazakhstan: 5 clues to understand what’s going on

Source: https://en.communia.blog/protests-in-kazakhstan/

The crackdown on protests in Kazakhstan has become internationalized: Russian paratroopers and Armenian, Tajik and Kyrgyz troops under CSTO mandate have entered the country to tackle demonstrators. Russian agencies speak of a joint action to confront “terrorists” and “bandits”, American ones of an attempt by Putin to “expand his influence”. Both render invisible the reality: from last Sunday to today, the Kazakh state has collapsed in the face of a mass strike that spread throughout the country, but which nevertheless is far from the level of workers’ self-organization that we have seen in Iran.

What happened?

Neither foiled coup attempt, nor Russian invasion: repression of a mass strike.

The chronology of the protests in Kazakhstan speaks for itself. Last Sunday, January 2, mass protests broke out in Zhanaozen after the government doubled gas prices. After the first attempts at repression, workers erected barricades throughout the city.

On the night of January 3 to 4 a wildcat strike began in the oil companies in Tengiz. Soon the strike spread to neighboring regions. At present, the strike movement has two main foci: Zhanaozen and Aktau, two of the main centers of the extractive industries.

Trucks with oil workers arrived to Almaty on January 4 and thousands joined the protest by occupying the city center and protesting in front of the city hall.

President Tokayev announced a state of emergency in the regions and on the morning of January 5 accepted the resignation of the government and proposed to replace the 100% price hike with a 50% hike. In the afternoon he announced that he had replaced his mentor, former dictator Nazarbayev as head of the country’s Security Council. After acknowledging that the protests had spread to more than half of the country, he announced that dozens of “rioters” had been “liquidated” and their identities were being identified.

Despite the crackdown, demonstrators continued to protest in front of Almaty city hall, overpowering police forces (see video). The building ended up in flames and rallies focused on the State Attorney General’s Office and the President’s official residence.

Also in Aktobe, the other major insurrectional hotspot, the local government building was stormed, unsuccessfully, by workers. The protests in Kazakhstan were far from exhausted.

The crackdown continued with mass killings and arrests throughout the night. In Almaty, protesters erected barricades, and several instances of security forces being disarmed were videotaped. In the face of resistance, police in several cities across the country either disbanded or joined the protests.

To deal with the collapse to which the protests in Kazakhstan had brought the state, Tokayev launched paratroopers against the demonstrators and asked the heads of the CSTO states to send troops to overcome the “terrorist threat,” calling the demonstrators he had tried to calm down shortly before “international terrorist gangs.”

Who are the protesters?

Neither international terrorists nor angry citizens: workers in struggle.

The protests in Kazakhstan are taking place in a broader context than the one being portrayed in the press. As we highlighted in our annual summary of struggles, one of the most significant developments of 2021 was that from Kazakhstan to the Donbass via Georgia, workers rehearsed forms of assertion as a class.

It is no coincidence that now one of the epicenters and the starting point of the protests in Kazakhstan is Zhanaozen. The wave of strikes in Zhanaozen in July was a reference throughout Central Asia. The movement, which, as we noted at the time, tended to develop into a mass strike despite trade union obstacles, has since then kept adding sectors and connecting workforces, maintaining a constant tension that has so far prevented an open brutal crackdown.

But their influence has gone far beyond local. In Kazakhstan there were more strikes in the first half of 2021 than in the previous three years combined, mostly centered in Mangystau and Zhanaozen.

In November, when an accident at the Karaganda mines pushed the mood of the miners toward a new big strike like the one in 2017, the unions jumped in to slash any attempt at a response. And practically at the same time the strike broke out at the Mangystaumunaigaz gas plants in the Zhanaozen region. The Zhanaozen reference turned the frustration of the miners into the ferment of a wildcat strike (=aside from the unions) that now broke out.

It is this accumulation and confluence of struggles bypassing the unions one by one – though not all – which explains the rapid mobilization from day one, when the government launched the gas price hike for domestic consumption and transport.

For instance, since the 2nd, the miners of Zhezkazgan in Karaganda, real epicenter of the wildcat strikes, have been demonstrating in front of the government building for a lowering of the retirement age, against inflation and for freedom of protest. Until the 5th, at the height of the state’s breakdown, the local political representatives did not even deign to receive the workers’ demands.

“To warm themselves, the demonstrators lit a bonfire and locals brought them food and tea. The miners tell RFE/RL that the demonstration is peaceful. Police are monitoring the situation but are not arresting anyone. As of 3:00 p.m. on January 6, about 300 people are near the akimat building. According to one of the participants of the action, there were many more demonstrators last night, and new participants are joining today.

In the Karaganda region, as in other regions, the Internet does not work, there are problems with cellular communication. Most operators report that only emergency calls are possible.”

What are the workers fighting for?

Neither anti-Russian “Euromaidan” nor “fight against corruption”, the basic needs of workers are the driving force behind the protests in Kazakhstan.

The trigger that has finally driven the strikes and protests in Kazakhstan to converge was the rise in the price of gas.

The extractive operations are in the middle of the desert and all goods are imported. The rise in gas for transportation means a general rise in prices and a loss of purchasing power that was already stretched to the limit by low wages.

“Gas prices, which we also produce, have skyrocketed. Everything depends on gas. If gas becomes more expensive, everything becomes more expensive.

Ordinary people already earn very little, and the situation will get worse. Let them reduce the price of gas to 50-60 tenge. Or raise our salaries to 200 thousand tenge. Otherwise, we will not survive when everything becomes more expensive.

The authorities say that there is not enough gas, that the plant built 50 years ago is worn out, outdated. And what have they done for 30 years?”

A worker, picked up by RFE

Plant managers, unionists and the local president tried to “explain” to the workers why they “needed” to raise prices (see video). The usual argument: the company would otherwise go into losses and jobs would be lost, that workers had to put up with it and hope for a better future. The workers responded that spinning “fairy tales” was not a solution to the problems, and politicians, trade unionists and managers left without persuading anyone. The workers had learned their lesson from previos struggles.

“Last year these companies began to be optimized on a large scale. Jobs were cut, workers began to lose their salaries, bonuses, many companies have become simple service companies.

When in the Atirau region the Tengiz Oil company laid off 40 thousand workers at once, it became a real shock for the whole western Kazakhstan. The state did nothing to prevent these massive layoffs. And it must be understood that an oil worker feeds 5-10 members of his family. The dismissal of one worker automatically condemns the whole family to starvation.

There are no jobs here, except in the oil sector and in the sectors that serve their needs.”

Are the protests in Kazakhstan really a revolution?

The protests in Kazakhstan have not reached a revolution, it is a mass strike which has not yet become self-organized.

What we are witnessing is not a revolution, but a mass strike which has not yet come to fruition, but which has nevertheless been enough to collapse the repressive apparatus of the Kazakh state.

Except in some companies of Zhanaozen, the struggles have converged but the assemblies and the committees elected by them have not. As a whole, the struggle is still far from the level of workers’ self-organization that we have seen in Iran.

The result is that the workers have discovered their own strength and appeared as a determining political subject at the national level… but they do not have the capacity to organize the power that has been left vacant.

This organizational weakness of the protests in Kazakhstan cannot but become a programmatic weakness. We saw it in Aktau last night. Union leaders took the lead in the protests with the acquiescence of the repressive forces and the regional government, reaffirmed the basic demands they opposed until recently, and called for maintaining order. Very symbolically, they planted a national flag – symbol of the interest confronted by the workers – as soon as they could.

Unions sow the path to defeat, as everywhere, but at the end of it there is something worse than a new cut to basic needs. Reinforced by Russian paratroopers and encouraged by the prospect of 2,500 Tajik and Kyrgyz troops promised to him immediately by the CSTO, President Tokayev has ordered the army to “shoot to kill” against the “20,000 bandits” he says are protesting in Almaty.

Why are the countries of the Russian area of influence sending troops then?

The ruling classes recognize and unite in the face of their enemy, while still hedging against their competitors in the face of a power vacuum.

The regional ruling classes were clear from the very beginning what lay beneath the protests in Kazakhstan. They know how to recognize the class enemy as soon as they see it on the move. Ten years ago they did not hesitate to repress strikers bloodily in Zhanaozen.

Nor do the European and Anglo-Saxon agencies and governments have any doubts. This time there is no support and messages as in Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, Georgia… or every time a bourgeois faction does something that could annoy Russian imperialism.

The “sacred union” between the factions of the bourgeoisie occurs automatically every time the proletariat enters the scene. Even between imperialist rivals. Suffice it to recall Berlin in 1953 or Budapest in 1956. In this case, when in addition Chevron is one of the oil companies directly affected by the strikes in Tengiz, nothing else could be expected.

But neither do they stop competing with each other nor do they stop trying to take advantage, even if it is only symbolic or propagandistic, of what in reality is a setback for all of them. Significantly, the English-language press and its echoes in other languages, despite not taking the issue to the front pages, have tried to play up the protests in Kazakhstan as a revolt “against corruption and inequality” that could also have repercussions in Russia itself.

Putin knows full well that he need not fear intervention by his imperialist rivals, nor will he suffer further economic reprisals for launching his elite troops against the protests in Kazakhstan. But it rightly fears, like other governments in the region, the economic costs and political risks of a power vacuum.

Its primary objective is to nip in the bud any possible revolutionary evolution of the protests in Kazakhstan. But there is more. Against its imperialist rivals it wants to show Russia’s ability to “maintain order” in its direct sphere of influence. And vis-à-vis the allied governments in Central Asia and the Caucasus, to send the signal that it is capable of keeping them in power in case they face a class mobilization like the one driving the protests in Kazakhstan….

…which is true, but only half true, because the key does not depend on him, but on the development of workers’ self-organization. One step beyond where the workers have gone so far and the assurances of the ruling class would dissipate.

Kazakhstan: The Working Class Attempts to Find its Voice?

ǀ Deutsch ǀ Español ǀ Italiano ǀ Nederlands ǀ Türkçe ǀ

On 2 January, in response to a sudden increase in gas prices, protests and blockades rose up in the oil city of Zhanaozen in the Mangistau region, western Kazakhstan. The revolt has now spread across the country, including Almaty, the largest city in the country, and Nur-Sultan, the capital. It has forced the current president, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, to sack his cabinet, declare a state of emergency and rescind the rise in gas prices (for six months). Despite this, the unrest continues. Tokayev has now branded the protesters “bandits” and “terrorists”, giving him an excuse to call in troops from the Russian-led CSTO (Collective Security Treaty Organization) alliance as a “peacekeeping” force, and has made it clear lethal force will be used to bring back order. Due to an internet blackout imposed by the state, it is difficult to gather exact information on the situation as it progresses. But so far dozens of protesters have been killed by the state.

Tokayev is the hand-chosen successor of Nursultan Nazarbayev, the former Prime Minister of the Kazakh SSR and the first President of Kazakhstan, who, despite the collapse of the Eastern Bloc, has continued to rule Kazakhstan behind the scenes until now. Like other former satellites of the USSR, the now formally independent Kazakhstan has been gradually overhauling its industry from state ownership to the private sector. It remains economically and politically attached to Russia, but in accordance with its “multi-vector” foreign policy, it has remained open to investments from China, the USA and the EU. Nazarbayev has been able to secure a degree of relative social peace during the last three decades, largely financed by the country’s lucrative oil, gas, coal and uranium reserves.

Since 2015 the government has been carrying out a fuel market reform, and as of the start of 2022 it has completed the transition to electronic trading for LPG (liquefied petroleum gas), removing state price caps. This was supposed to address ongoing domestic shortages of LPG (used by a majority of Kazakhs to power their cars) but instead it effectively doubled its price overnight at gas stations across the country, sparking the most serious challenge to the regime since the country’s independence.

The current wave of protests began in Zhanaozen. This is significant because it was in this city that back in December 2011 the regime sent in police to quell a series of strikes of oil workers demanding pay rises. According to official sources, at least 16 workers were killed during the suppression of these strikes, although the real tally is likely much higher. We wrote about it at the time. More recently, poor pay, inflation and unemployment, exacerbated by the pandemic, have led to growing labor unrest in the region, to the point where “in the first half of 2021, there were more strikes in Kazakhstan than in the entire 2018 to 2020 period.” No surprise then that after the current protests started, “on the night of 3 to 4 January, a wildcat strike began at the Tengiz Oil enterprises”, and has since spread to neighboring regions. There are videos of workers spontaneously walking out and holding mass meetings. On the international markets there are already worries how this will affect the export of oil and uranium ore. But the internet blackout makes it all the more difficult to find out what exactly is happening on the ground and how widespread these strikes really are.

What we are seeing is undoubtedly another manifestation of the global crisis of a stagnating capitalism. This crisis goes back years and involves far more than gas prices. The protests are a response to the worsening situation of the working class, all in a country where “162 persons, are worth more than $50 million, which equates to around 50% of the total wealth of the population”. The movement is taking on political forms and other demands are already being raised, among them “reduction of food prices, taking measures against unemployment, solution to the drinking water shortage, resignation of the government and local authorities.” It is hard not to see similarities with the current situation for the working class in Iran, where since June around 100,000 workers in the petrochemical industry have been on strike, in response to poor wages and conditions, the militarization of labor, an uncontrolled spread of Covid-19 which hits workers hardest, and a climate change-induced drought which has resulted in riots over water shortages. We have been covering this working-class upheaval for the second half of 2021, where the workers are demonstrating excellent leadership capacities in directing their struggle. The problems faced by workers in Kazakhstan are therefore not unique to their own country and are shared by workers across the world, who also share the ability and sometimes, as we see in Iran, the will, to fight back as a class.

The initial concessions by the government seem not to have worked as intended, so it has defaulted to what it knows best: brute force. In a television address to “the nation” on 7 January, Tokayev made it very clear: “Those who do not surrender will be eliminated… law enforcement and the army have been given the order by me to shoot to kill without warning.” Like in Belarus – or indeed many of the other revolts of recent years – what we are seeing here is a movement where the working class plays a key role but where it is not calling the shots. Before the movement in Belarus was drowned in repressions, we warned:

“As is usually the case, the material reasons that forced the workers into the streets are linked to the worsening economic crisis, to precarious living and working conditions. (…) In the absence of a communist programme that is rooted in the most conscious sectors of the proletariat (which in itself does not guarantee the class itself can overcome the disorientation which Stalinism and the post-Stalinist system have left it in) the working class is prey to the professional “consensus makers” deployed by the bourgeoisie to protect their interests. Once this is achieved, our class is faced only with open and brutal repression.”

So as always, we have to repeat: “without the revolutionary party, every revolt will exhaust itself within the system.” If the working class fails to put forward its own program and organization, other forces will surely fill the vacuum: be they liberal or nationalist. It is our job as communist militants to try to highlight examples of working class militancy as we are seeing in Kazakhstan, and to try to reach workers in Kazakhstan with a message that rejects subordinating the working class to other parties, and which calls for the working class to act independently as a class to put forward its own program. This is necessary so that in the future global struggle of our class, our class can boldly seize the moment, rather than be victim to the repression and cynical machinations of the bourgeoisie.

Solidarity to the working class of Kazakhstan and all countries! Felix (IWG) and Dyjbas (CWO)

7 January 2022

Statement by Russian anarcho-syndicalists and anarchists on the situation in Kazakhstan

Source: https://aitrus.info/node/5884/

ǀ Español ǀ Français ǀ Italiano ǀ Русский ǀ

We, Anarcho-syndicalists and Anarchists of Russia express our full and complete solidarity with the social protest of the working people of Kazakhstan and send them our comradely greetings!

The current explosion of social protest in Kazakhstan, one of the most outstanding and brightest since the beginning of the new century, has become the apogee of the wave of the strike struggle of oil workers and other categories of workers in the country, which has not stopped since last summer.

The working people of Kazakhstan gradually recovered from the terrible massacre of the proletarians, organized in 2011 by the dictatorial regime of Nazarbayev, and began to consistently seek higher wages and the ability to create trade unions and other workers’ associations. The poverty of the majority of the population, the cruel exploitation of labor, the rise in prices, daily oppression and lack of rights made the position of the working person unbearable and forced him to rise to protest actions.

The last straw was the layoffs of tens of thousands of oil workers in December 2021, the introduction of a “sanitary” dictatorship under the pretext of “fighting the pandemic” and a draconian increase in gas prices. On January 3, a general strike of workers began in the Mangistau region, which soon spread to other regions of the country. In the former capital of Kazakhstan, Almaty, clashes erupted between protesters and repressive forces; there are tens or even hundreds of people killed and wounded. During the protests, disadvantaged people, primarily young unemployed and internal migrants, committed acts of popular expropriation, destroying many large shopping centers, shops and bank branches. In a number of cases, the troops refused to open fire on the rebels.

The protest in the country is spontaneous and uncoordinated; therefore, its participants put forward a variety of, often contradictory, slogans and demands. We, as anarchists, support, first of all, those of them which have a distinctly and unequivocally social orientation and sharply distinguish the strike and uprising in Kazakhstan from the numerous electoralist protests and political coups of recent years. These demands were spread during the protest rallies and in social nets: the abolition of the increase in gas prices; increase in wages by 100%; cancellation of raising the retirement age; taking measures to combat unemployment; abolition of compulsory vaccination against COVID-19, lockdowns and discriminatory segregation measures, etc.

In an effort to end the social revolt and gain time, the frightened regime was forced to make concessions: to declare a drop in gas prices, freeze prices for “socially important” goods for 180 days, dismiss the government and remove the de facto dictator, billionaire Nazarbayev, from the post of head of the Security Council of Kazakhstan. But none of this helped. Western oil companies insistently demanded that President Tokayev restore the capitalist order. The country’s rulers imposed a state of emergency and curfews, banned rallies and strikes, and launched punitive operations against protesters and rioters, spilling streams of blood and arresting thousands of people.

At the request of the Kazakhstani regime, troops from a number of countries of the military-political bloc headed by the Russian Federation are being brought into the country to suppress social protests. They are called upon to fulfill the role of a gendarme for World Capital and trample the flames of social rebellion until its example, slogans and demands spread to other countries, engulfed in workers’ strikes and mass protests against the widespread “sanitary” dictatorship and its apartheid.

We, Russian anarcho-syndicalists and anarchists, strongly condemn any suppression of social protests by the working people of Kazakhstan and the shameful counter-revolutionary foreign intervention led by the Kremlin.

We condemn any attempts by politicians of all stripes to use the social protest of Kazakhstani workers in order to climb to the top of power by themselves and redistribute property in their favor.

We stand firmly, resolutely and without the slightest hesitation on the side of the current social revolt in Kazakhstan and call on the working people of Russia and the whole world to show practical solidarity with it.

FULFILL SOCIAL REQUIREMENTS OF KAZAKHSTAN WORKERS!

STOP SUPPRESSING PROTESTS IN KAZAKHSTAN AND REPRESSION AGAINST THEIR PARTICIPANTS!

FREEDOM TO ALL ARRESTED PROTESTORS!

NO FOREIGN INTERVENTION!

SHAME TO INTERVENTIONISTS!

Anarchist Initiative StopTotalControl

Commission of Information of CRAS, IWA section in the Region of Russia

Kazakhstan: strikes and riots teeter the regime

Source: https://www.pcint.org/01_Positions/01_03_en/220110_kazakhstan-en.htm

ǀ Español ǀ Français ǀ Italiano ǀ Čeština ǀ

The protest and revolt movement that has been affecting the country for a week was triggered by the sudden decision of the government to double the price of gas and petrol; as soon as this announcement was made, protest demonstrations by workers and unemployed began to take place on Sunday morning, January 2, in the oil city of Zhanaozen, in the west of the country (Mangystau region) (1).

During this same day, protest actions (rallies, sit-ins, etc.) spread to the nearby port city of Aktau to demand the withdrawal of the increases – or the doubling of wages! The next day the protest continued to spread despite the deployment of the police and more and more companies stopped work; social networks broadcasted scenes of fraternization between police and demonstrators. On January 4, although the prefect (the “akim”) and the minister of energy announced a reduction in the price of gas and petrol for the inhabitants, the strike was almost general in the whole Mangystau region (oblast), where part of the country’s extractive industries are concentrated.

Also on 4 January, at the other end of the country, miners in the Karaganda region went on strike, while demonstrations and blockades spread throughout most of Kazakhstan. In several places the demonstrators attacked the symbols of the regime: statues of the former autocrat Nazarbayev, who continues to pull the strings as president for life of the “National Security Council”, official buildings and even police stations. The departure of Nazarbayev and his creatures (including Tokayev, the current president) was at the center of the slogans.

The regime responded by dismissing the government and Nazarbayev himself, and by declaring a state of emergency; it unleashed a bloody crackdown, particularly in the economic capital Almaty on Wednesday night (more than 100 deaths according to the Health Ministry). Faced with the social explosion, the president asked for Russian help, which was immediately granted: 3,000 Russian soldiers, flanked by a handful of soldiers from other countries, arrived on Friday 7 January. The same day Tokayev declared on television that he had “given the order to shoot to kill without warning”. On Saturday, journalists in Almaty were still reporting gunfire in some parts of the city, but the president said that “constitutional order had been restored”.

It was restored in blood, according to the authorities themselves: on 9 January the official toll of the repression was more than 160 demonstrators killed by bullets, several thousand injured, and 6000 arrested.

This “order” is the capitalist order, sanctioned by all imperialisms; if China, in a message from Xi Jinping, congratulated Tokayev for the “strong measures” taken to quell the revolt, the more hypocritical Western imperialisms called for “restraint” “on all sides”, putting the demonstrators and the murderous forces of repression on the same level; no one protested against the Russian intervention. This is because Kazakhstan, rich in oil and other minerals, has received significant investments from Western companies, including American ones: fearing social unrest that could jeopardize their capital, they see in the Russian intervention a guarantee against this danger…

For several years, Kazakhstan, a geographically large but sparsely populated country (19 million inhabitants) that occupies a strategic position in Central Asia, has experienced strong economic growth, based on oil and gas (despite some setbacks in its dream of becoming the Kuwait of Central Asia), but also on coal and uranium (world’s largest producer). It had taken advantage of this to emancipate itself from Russian domination; it had drawn closer to China and the West, signing a military agreement with Italy, one of its first clients, and then with the United States; it had also drawn closer to Turkey by joining the “Organization of Turkic States”, an embryonic alliance of the Turkic-speaking countries of the former USSR with Ankara. Turkish President Erdogan phoned Tokayev on 6 January to assure him of his support and to offer him “his experience and technical expertise”; but the experience and expertise of the Russian godfather are far superior…

The proletarians have not benefited much from the economic prosperity; the regime has continued to use repression against any attempt at independent workers’ struggle and organization; police brutality and torture are common. In 2011, it brutally repressed a strike by oil workers in Zhanaozen to improve their conditions: the police shot at the striking demonstrators, killing at least 16 people.

Some analysts, including in the West, claim that the current unrest is at least partly caused by internal rivalries within the regime. It is quite possible that there are attempts to settle scores between bourgeois cliques in the current events; but it is undeniable that their cause is the increasingly intolerable situation of the proletarians and the poor strata, in a situation of economic crisis which leads to layoffs (40,000 layoffs in the Tengiz oil field in December, with more planned) and inflation (officially 8% but in reality much more). The proletarian character of the revolt is demonstrated, if it were necessary, by the fact that it started from a strike movement based on demands for improved living and working conditions and higher wages. The petty bourgeois democrats indicate to the proletarians the objective of a “democratic Kazakhstan”, rid of the clique in power; some pseudo-socialists like the neostalinists of the “Socialist Movement of Kazakhstan”, demand the return to the Constitution of 1993, supposedly more democratic.

But it is not for a simple change of facade of the regime that the proletarians must struggle, because, by leaving intact the capitalist mode of production, such a change would not modify their fate. The struggle for political and trade union freedoms is undoubtedly necessary, but only if it is part of the struggle against capitalism, which exploits them and reduces them to misery. Only the proletarian class struggle can have the strength to put an end to capitalism, by uniting proletarians over the borders: this is what the bourgeois and petty bourgeois democrats fear…

The current social explosion has shaken the regime, it has shown the power of the working class and the gravity of the social tensions accumulated under capitalism; tomorrow the revolutionary struggle of the proletarians of Kazakhstan, Russia and all countries, under the leadership of their international class party, will overthrow all the murderous capitalist regimes, and will avenge their countless victims.

While the economic crisis inexorably pushes the proletarians to revolt, this is the perspective that must guide them in their struggles, in Kazakhstan and everywhere!

(1) We take the information from the site socialismkz.info

International Communist Party

January, 10th 2022